As growers, PCAs, or irrigation specialists, we all know the word “leaching” and hear it more often than not.

Whether it’s because of the sustainable groundwater issues we are facing, nitrate issues, or the need to keep important nutrients and fertilizers in our soil, the word “leaching” plays a major role in all of our lives.

Regardless of your stance on certain issues facing the grower, we can all better understand leaching and its effects on soil, water usage, and overall plant health. If we understand the word and its role in soil and plant health, we can become better stewards and producers as well.

We all know that water in soil moves both downward and horizontally after an irrigation or rain event. Depending on soil conditions, it can really move in any direction. Water moves through the open pores in soil particles and fills the pore space. Depending on soil type, the various soil particles can either hold water more tightly or can simply hold more water than other particles and soil types (that’s a lesson for another time). But along with that water, air, also shares the pore space within the particles.

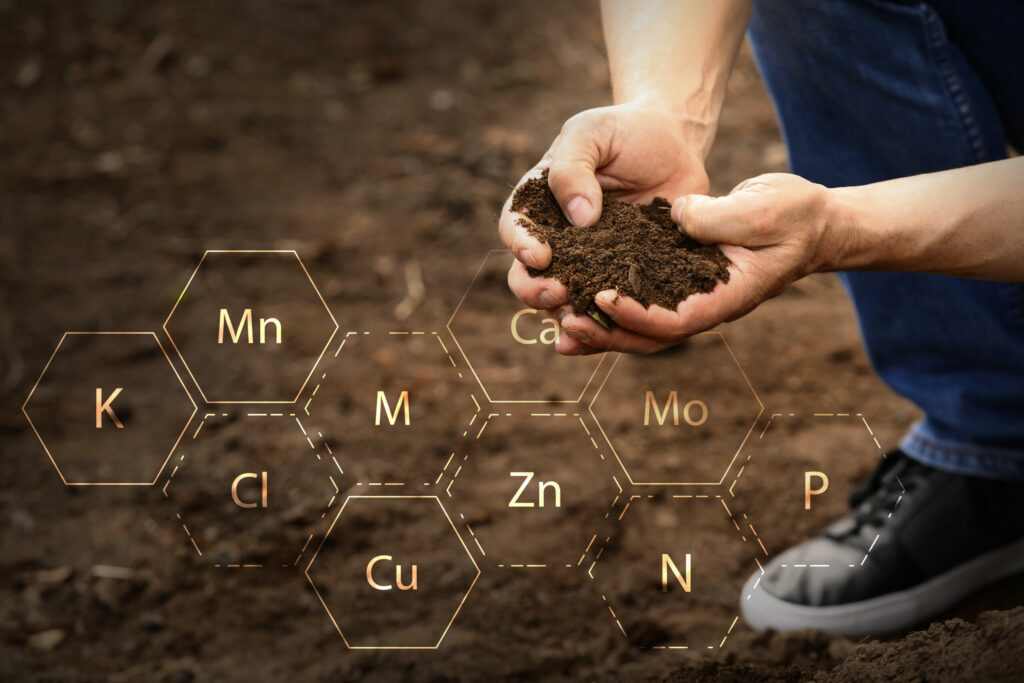

When pore space is filled with water, we know the soil has reached saturation and there is no more available air or space in the soil (also known as becoming anaerobic). Once saturation is reached, any additional irrigation or rain will cause leaching. During the leaching period, we lose valuable plant nutrients in the soil, which can sometimes change the soil structure all together. Understanding this is vital as growers, as we tend to put a significant amount of resources toward improving our soil health, whether it be with our soil nutrient programs, fertilizers, or even the cost of water.

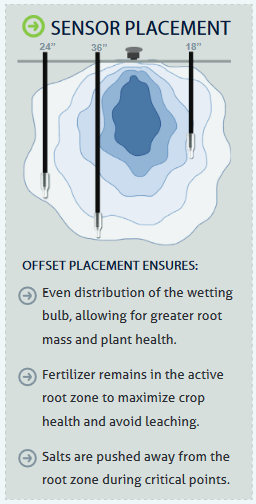

Knowing how full the soil is, and how the soil particles are holding on to the water (soil tension), and knowing what depth moisture is at, are the only ways to control or prevent leaching. At times, such as during the winter months, we encourage some leaching — to push salts and other harmful minerals from the root zone. Other times, during the growing season in particular, we work to prevent leaching to keep valuable nutrients in the root zone and encourage plant uptake. This is key in our fertilizer management programs, helping to ensure an optimal wetting pattern (as seen by the diagram at right), and preventing us from pushing costly nutrients beyond crop reach.

Knowing how full the soil is, and how the soil particles are holding on to the water (soil tension), and knowing what depth moisture is at, are the only ways to control or prevent leaching. At times, such as during the winter months, we encourage some leaching — to push salts and other harmful minerals from the root zone. Other times, during the growing season in particular, we work to prevent leaching to keep valuable nutrients in the root zone and encourage plant uptake. This is key in our fertilizer management programs, helping to ensure an optimal wetting pattern (as seen by the diagram at right), and preventing us from pushing costly nutrients beyond crop reach.

In almonds, for instance, the majority of the active root zone (where plants most actively draw water from the soil) is in the top three feet. We also know that a soil tension reading of 0 kPa (0 centibars), is an exact measurement of saturation. That said, if a grower applies fertilizer during an irrigation, and continues to irrigate past 3 feet with soil tension reaching 0 kPa, some of the fertilizers, depending on the form in that application will have pushed past the active root zone.

” With the cost of fertilizer and nutrient programs today, it is extremely important to utilize the nutrients you put in the ground …”

Once it reaches this point, the application won’t be used or absorbed by the most active roots. Again, with the cost of fertilizer and nutrient programs today, it is extremely important to utilize the nutrients you put in the ground, know where they’re at, and make sure they’re available to crop. If we are encouraging leaching to purge harmful minerals, we should also understand the proper timing and when we’ve applied enough for that particular irrigation event.

Often, irrigators don’t know exactly when they’ve reached that leaching point, and an extreme amount of water is applied to push salts from the soil. Sometimes, it can take 36 hours to reach that point, and in other instances even longer. Either way, knowing where the water is and anticipating when that leaching point occurs, is everything.

Currently, the most efficient way to monitor and anticipate when that leaching point occurs is to monitor root-zone moisture via real-time soil tension data — which notifies the grower when tension drops to 0 kPa, or saturation.

Whether you’re pushing salts from the soil or keeping valuable nutrients in the root zone, it is our job as stewards of the land to do our part and keep an eye on our soil. But you can’t do that without putting the right technology in place.

Understanding what’s going on beneath the surface and how the soil profile is reacting to each irrigation is critical to any irrigation management program.

By knowing this, we can ensure we keep our soil in its best form, use only the water needed to reach certain points in irrigation, and make the crop as healthy and productive as possible.